American Origins of Decentralized Finance

Early America's Currency Struggles and Future Crossroads

By Anthony Benjamin, Normal Finance

10 Minute Read

Summary

The journey of decentralized finance (DeFi) is reminiscent of America's early financial innovations. Colonial Americans faced significant challenges due to a scarcity of hard currency, leading to the creative use of commodities like tobacco as currency. As the nation progressed, decentralized financial practices continued to emerge, influencing significant infrastructure and trade developments. The creation of Visa in the 1970s as a decentralized network for value exchange mirrored these earlier experiments. Today, DeFi represents a modern evolution, utilizing blockchain technology to enable secure, intermediary-free transactions. Understanding these historical parallels provides insight into the potential impact of DeFi on global finance, highlighting its role in enhancing financial democratization and innovation.

Keywords: decentralized finance, blockchain technology, cryptocurrency, economic history, colonial America, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, tobacco notes, banknotes, Civil War, Federal Reserve, monetary system, Visa, treasury bonds, reserve currency.

In the coming years, decentralized finance (DeFi) will reshape the financial landscape. Driven by blockchain technology, DeFi enables secure and efficient financial transactions without central intermediaries which will liberate financial services and liquidity. These new financial tools offer unprecedented opportunities for growth and innovation. They beckon a future that upends legacy processes and reveals new horizons. Yet, this is not the first time America has witnessed such a bold restructuring of its financial underpinnings and means of doing business.

Since its inception, America has been at the forefront of economic advancement. This progress is core to how Americans have retained the highest standards of living, served as custodians to the world's reserve currency, and been the center of world commerce and innovation. While precipitated by necessity, transformative shifts in the financial landscape have unleashed unexpected economic growth, goods, and services all drastically improving the quality of life for everyone involved.

Early America’s Decentralized Financial System

In the 1700s, at the frontiers of Western civilization, colonial Americans faced an existential crisis. While having the highest wages in the world and unprecedented purchasing power of raw material, Americans lacked hard specie, gold or silver currency. Specie was required to pay taxes and settle accounts managed in London for financing land and manufactured goods. As mercantilist practices siphoned specie away from Americans, often, they were forced to sell off productive assets to pay their debts. They were severely limited in their ability to exchange their goods and services and unable to accumulate capital.

Many Americans resorted to trading with tobacco as a currency. The crop was a stable commodity backed by a liquid market in London. Fluctuating yields of planting seasons and the resulting volatile prices encouraged speculation in the commodity by American elites. This home market provided accessible liquidity and led to the creation of large, public, tobacco warehouses. These warehouses were eventually formalized with transferable inspection certificates, which verified the quantity and quality of the crop. Many tobacco warehouse certificates became regulated by states to standardize the inspections, quality controls, and procedures. This public policy measure created a reliable, decentralized system for tobacco notes to be circulated as a currency with underlying value.

As the lack of specie troubled the economy and use of tobacco notes grew, the need for a more flexible and scalable monetary system became evident. In 1729, Benjamin Franklin was already advocating for such a system of paper currency.1 He would later pioneer it through his printing business establishing standardized bank notes and anti-counterfeiting printing methods. In place of scarce specie, Franklin helped state, charter, and private banks adopt their own bank notes that were backed by local land and mortgages.

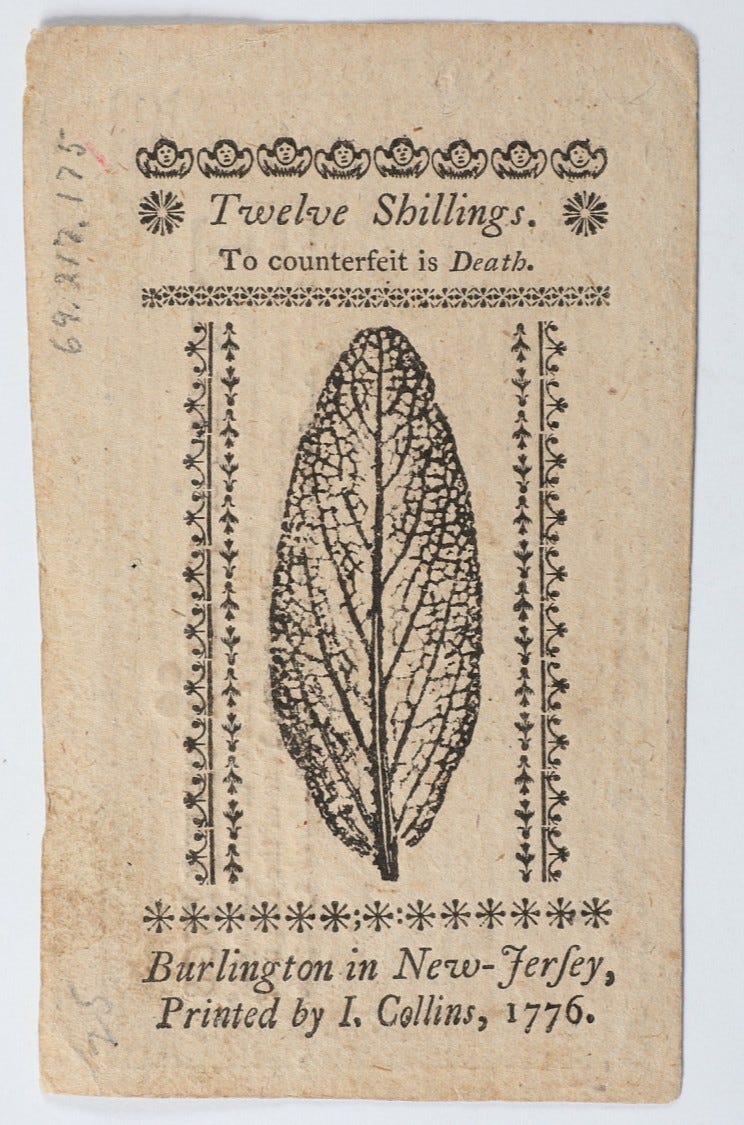

“Twelve Shillings. To Counterfeit is Death.” A colonial banknote issued by the state of New Jersey as legal tender during the American Revolution. It features a sage leaf cast print originally developed by Benjamin Franklin as one of many anti-counterfeiting measures.2 The note’s severe message reflects the dire currency situation of the time; Americans caught distributing counterfeit currency were sentenced to execution.3

These varying entities of regulated banks created a decentralized network of credit creation. They allowed for rapid innovation, market investment, and flow of trade. They even helped facilitate large, unprecedented infrastructure projects such as the Erie Canal when the federal government was unwilling to help.4 However, they were limited by the speed of information concerning transactions, contracts, and credit. The resulting bank note arbitrage between regions created a distance-based value for bank notes; the farther a customer was from the note’s issuing bank, the less valuable the note was considering the distance and time it took to redeem its underlying asset. Moreover, the farther that collateral land was from navigable waters or rail, the more speculative the underlying value was.5 These shortfalls in speed of information, verification, and oversight made wildcat banks on the frontier unstable and risky. However, these riskier banks provided a medium for exchange where it was not previously possible and their drawbacks were being ameliorated by telegraph and railroad developments.

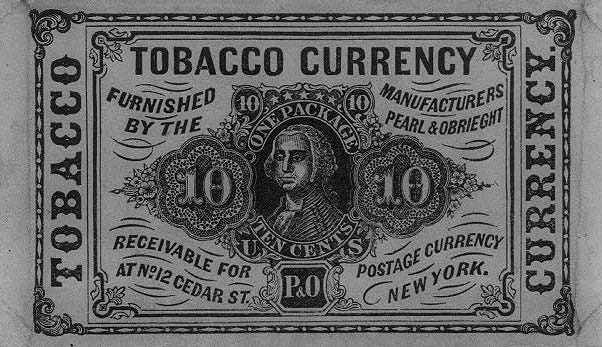

A 10 Cents "Tobacco Currency” note issued by Pearl & Obrieght of New York in 1863. Redeemable for a package of their tobacco and used for the exchange of other goods due to rampant inflation and shortage of specie.6

Early in 1861, the start of the Civil War put the circulation of currency under immense pressure, risking the exhaustion of specie and widespread banknote inflation. By the end of the year, Congress suspended specie payments nationwide which was quickly followed by the first issuance of greenbacks, a national legal tender with no backing. In 1863, facing further inflation, Congress enacted a national banking system which issued uniform banknotes. These national banknotes were all backed by central government bonds that paid interest in gold. Decentralized banking would continue to operate and their currencies circulate until 1865 when Congress implemented a 10% tax on their transactions.7 The wartime crisis allowed for the first successful, centralized national banking system and national currency after many decades of failed attempts of Alexander Hamilton’s American System due to political opposition.

After the centralization of U.S. finances, decentralized financial practices would still appear across the country. Industrial communities, lumber camps, and mining towns would use scrip, a localized currency, to address cash scarcity. This practice facilitated trade and enabled productive capital to work at scale in remote areas where banking was unavailable. Towns would use their own scrip during depressions to ensure economic activity. Even so, scrip lacked transparency, autonomy, and equitable governance of its distribution. Labor unions campaigned against these intrinsic flaws often exploited by employers.8 Furthermore, improved access to banking eventually made the practice redundant and significantly reduced its use.

The Modern U.S. Economy and Decentralized Finance

In 1913, the national banking system would further centralize to address the liquidity crises during the frequent depressions of the decades prior. The Federal Reserve Act instituted modern monetary policy for adjusting the money supply and interest rates while providing a lender of last resort for stabilizing the economy. The Federal Reserve became the single, central authority and intermediary of a trust system marking a critical pivot in the history of U.S. finances.

While the Federal Reserve’s centralization brought stability to U.S. finances, it also concentrated control. With the rapid innovation of communications and computing, innovators in finance began to explore decentralized alternatives that could restore flexibility and autonomy to financial systems. Credit card precursors, such as charge cards, store credit, diners club cards, and the BankAmericard system, helped bridge the gap from old practices of issuing scrip. Decades later, Dee Hock confronted the inefficiencies of a fragmented yet preeminent BankAmericard system and envisioned a new model for value exchange. Inspired by the limitations of centralized financial intermediaries, Hock founded Visa in the 1970s as a decentralized, electronic network where member banks shared ownership and governance. His chaordic philosophy—balancing chaos and order—challenged rigid framework, offering a scalable, cooperative system that echoed America’s earlier decentralized experiments and foreshadowed the trustless, intermediary-free ethos of modern decentralized finance.

In 1969, Hock convened a group of bankers in Sausalito, California, to reimagine the credit card system. He posed a bold question: “If anything in the world were possible, if there were no constraints whatever… what would be the nature of an ideal organization to create the world’s premier system for the exchange of value?” After days of debate, Hock proposed a decentralized network where banks would cooperate as equals, sharing ownership and governance for facilitating transactions and providing a network. This led to the creation of National BankAmerica, which became Visa in 1976.9

Visa’s structure was groundbreaking. It was owned by its member banks, with no single entity dominating. Simply, it was a member-owned cooperative with decentralized governance. The system facilitated transactions through a network of bits, guaranteeing settlements between issuing and acquiring banks without centralized control. It reduced the trust required among participants creating a trustless system, as Visa’s role was limited to ensuring the network’s integrity. This design allowed thousands of banks and businesses to compete and cooperate, creating a scalable, global payment system.

DeFi Today and Its Significance

Hock’s vision extended beyond credit card payments. He saw money as “guaranteed, alphanumeric data” in a microelectronics environment, a perspective that anticipated digital currencies. His decentralized model challenged the command-and-control structures of traditional finance, emphasizing efficiency and transparency. While Visa no longer operates as a cooperative since its 2008 IPO, its original structure and philosophy would inspire the creation of cryptocurrencies for a DeFi future economy. This recent history will have to be covered in a future article with special attention to the incremental technological developments and their implementation.

Current international banking relies heavily on networks like Visa and have fundamentally inherited its decentralized structures that facilitate interoperability. This makes them readily adaptable to decentralized systems and many institutions are already planning to adopt them. For example, Visa is currently piloting a tokenized asset platform allowing banks to issue and manage fiat-backed tokens.10 The introduction of decentralized financial systems is disruptive, yet it remarkably further improves cooperation among legacy institutions.

These DeFi developments today are reminiscent of past periods of economic shifts. A reevaluation of forgotten American history can be a guide for this rapid change and help direct DeFi’s evolution. Meanwhile, colossal economic forces, like the U.S. debt burden, great power competition, and rampant AI-driven automation, will shape the landscape that DeFi operates in. For instance, as a result of the 2025 global trade conflict, U.S. Treasury bonds and stock market broke their traditional inverse relationship while crypto markets sharply diverged from both. This is just the beginning of DeFi becoming a hedge against uncertainty and an international reserve as its ability to provide liquidity and exchange value grows.

About the Author

Anthony Benjamin is a peer reviewed, published author in research and for CSIS currently working for Normal Finance providing decentralized authorization governance, smart contracts, and dynamic indexes for cryptocurrency markets. He writes on the value of decentralized finance and U.S. economic history. Anthony is active on LinkedIn. Reach out to join the 2,000+ member Discord server or exclusive Telegram chat.

“Founders Online: The Nature and Necessity of a Paper-Currency, 3 April 1729.” 2019. Archives.gov. 2019. founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-01-02-0041.

“12 Shillings, New Jersey, 1776.” 2025. National Museum of American History. 2025. americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object/nmah_1986778.

Whiting, John. 1844. Revolutionary Orders of General Washington. Edited by Henry Whiting. New York City: Wiley and Putnam.babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081902094&seq=126.

Miller, Nathan. 1962. The Enterprise of a Free People: Aspects of Economic Development in New York State During the Canal Period, 1792–1838. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. archive.org/details/enterpriseoffree00mill_0/page/n5/mode/2up.

Rolnick, Arthur J., and Warren E. Weber. 1982. “Free Banking, Wildcat Banking, and Shinplasters.” Quarterly Review 6 (3). doi.org/10.21034/qr.632.

“Tobacco Currency - Furnished by the Manufacturers Pearl & Obreight.” 2015. The Library of Congress. 2015. loc.gov/item/2001697792/.

Million, John Wilson. 1894. “The Debate on the National Bank Act of 1863.” Journal of Political Economy 2 (2): 251–80. doi.org/10.1086/250204.

Lewis, John L. 1925. The Miners’ Fight for American Standards. Indianapolis: Bell Publishing. babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015000335409.

Sheffield, Cuy. 2023. “Dee Hock Crypto and the Chaordic Age.” Visa.com. 2023. corporate.visa.com/en/sites/visa-perspectives/trends-insights/dee-hock-crypto-and-the-chaordic-age.html.

Visa Inc. 2024. “Visa Introduces the Visa Tokenized Asset Platform | Visa.” Visa.com. Visa Inc. October 3, 2024. usa.visa.com/about-visa/newsroom/press-releases.releaseId.20881.html.

Beautiful history on decentralized finance in America. DeFi and cryptocurrency are powerful forces in the world of data and tech we live in now. Excited to Make Crypto Normal together!

Under a non-fractional financial system (DeFi) do you think we will see similar levels of free banking? Or will the lack of leverage limit the system?